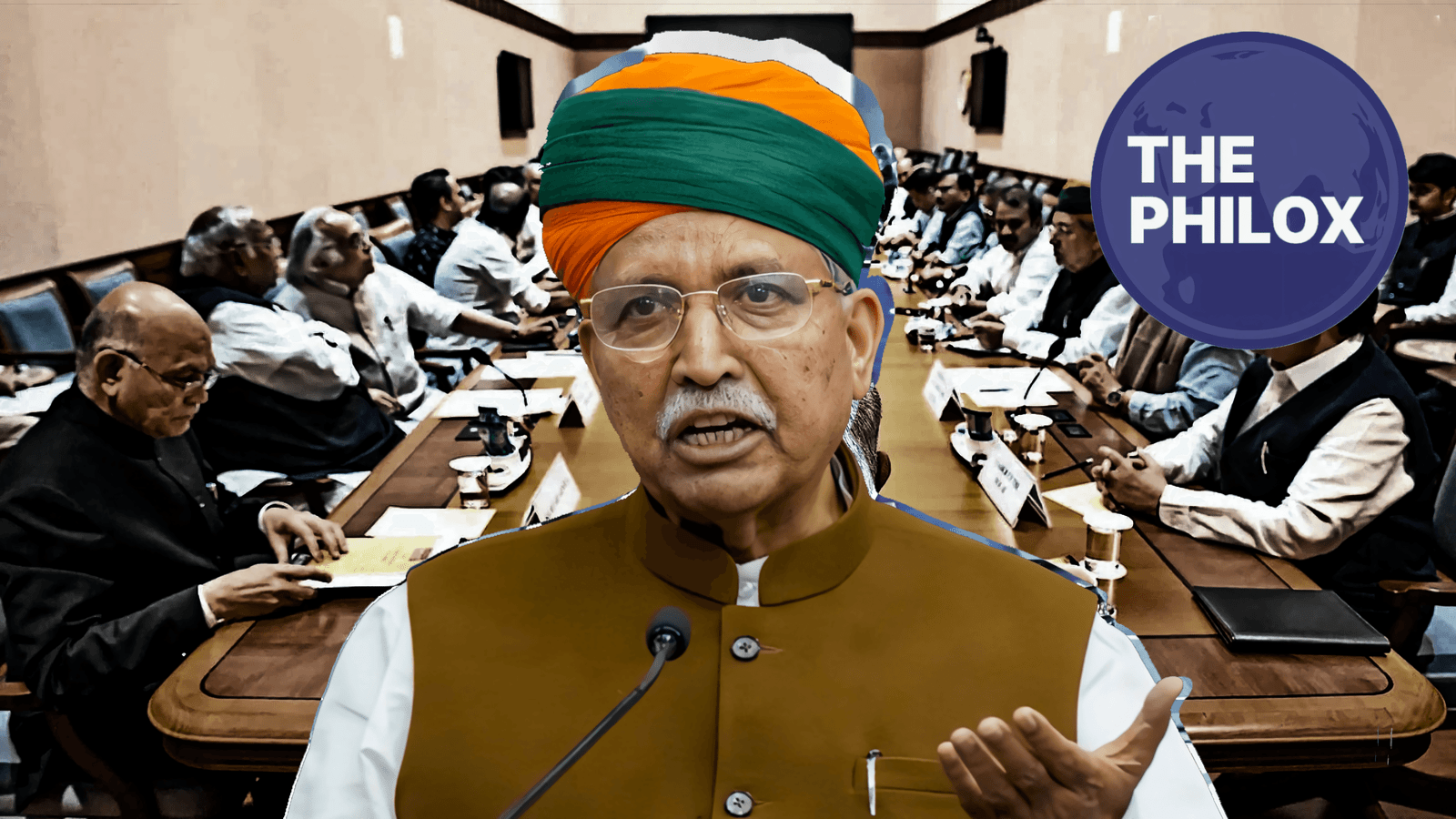

As Union Law Minister Arjun Ram Meghwal indicates a fresh attempt to establish the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) in 2025, the argument over judicial appointments in India is about to be revived as well.

But this time the structure is supposed to avoid the divisive veto power that resulted in the Supreme Court rejecting the previous NJAC Act in 2015. Delivered before a legal conference in New Delhi, Meghwal’s remarks in March 2025 once more put judicial reforms at the core of India’s governance debate.

While addressing issues over too strong executive control, which had already resulted in constitutional invalidation, the proposed revisions seek to promote more openness in court selections.

NJAC’s rise and fall: the 2014 Act and its demise

Originally designed to replace the long-standing collegium system for selecting judges to the Supreme Court and High Courts, the NJAC was first envisioned through the 99th Constitutional Amendment Act in 2014.

Involving members from the executive, court, and civil society, the NJAC was meant to provide a more ordered and participatory method. Under the 2014 approach, the commission comprised two eminent personalities, the Union Law Minister, the Chief Justice of India, and two senior Supreme Court judges.

The clause allowing any two NJAC members to have a veto over judge selections, however, caused a major source of dispute. Critics contended that this clause compromised the court’s independence especially considering two members from the executive branch.

Declining the NJAC Act and the 99th Constitutional Amendment in 2015, the Supreme Court’s Constitution Bench cited a breach of judicial independence—a vital element of the Constitution’s basic framework.

The decision confirmed the primacy of the collegium system, notwithstanding long-standing complaints about its lack of responsibility and transparency. Although the court considered this as a triumph for constitutional values, detractors—including parts of the government and legal fraternity—kept wondering if the collegium system was really the best way for appointments of judges.

Reviewing NJAC: Meghwal’s Suggestion for a Complementary Approach

Almost ten years after NJAC was denied by the Supreme Court, the argument has resurrected under the direction of Arjun Ram Meghwal with fresh intensity.

Meghwal alluded at a fresh attempt to reinstate NJAC—this time, properly crafted to accommodate court concerns while guaranteeing executive input—during a high-profile legal symposium in New Delhi, in March 2025.

The elimination of the veto authority once granted to two members—including the Union Law Minister—marks a major break from the previous system. This action seeks to reassure the court that its independence will not be compromised while yet adding some openness to the choosing process.

Meghwal’s announcement comes after a series of negotiations starting in February 2025 when the administration sought a reasonable substitute for the collegium system by consulting constitutional scholars, retired judges, and legal experts.

These negotiations produced a six-member NJAC proposal including two Supreme Court judges, two prominent persons, the Union Law Minister, and an opposition representation.

Two The main issue in 2015 was eliminating the prospect of unilateral executive involvement, hence this composition is meant to provide more representation.

This fresh drive for NJAC coincides with increased criticism of the collegium system itself at this point.

The system was attacked for lack of openness in 2023 with claims of partiality and unclear standards for choosing. The administration has used these complaints to contend that a rebuilt NJAC may provide a more orderly and responsible appointment system.

Legal and Political Reactions to the New Jersey AC Model

Although early signals point to the Supreme Court approaching any modifications with caution, the court’s reaction to Meghwal’s suggestion is yet unknown.

Chief Justice of India (CJI) D.Y. Chandrachud has said in January 2025 on the importance of constitutional checks that any appointment system had to protect judicial independence. Though not specifically criticizing NJAC, his comments capture the court’s long-standing opposition to political intervention.

Should the government move forward with a new NJAC proposal, it will probably come under close examination by courts, especially with regard to whether the new model effectively safeguards the separation of powers.

Political responses to the idea should be mixed. While the opposition may object about the executive’s participation in judicial selections, even in a weakened form, the prevailing government may contend that this action improves openness and responsibility.

Nonetheless, the six-member panel’s inclusion of an Opposition representative could act as a counterbalance to any government unilateral decision-making concerns.

More general judicial reforms under Meghwal’s direction

Meghwal’s larger court reform program includes the NJAC resurrection, which is not a stand-alone project. He also supported the founding of the Mediation Council of India in March 2025, an organization meant to institutionalize alternative dispute resolution systems.

This is consistent with the government’s goal of lowering court backlog and advancing quicker conflict settlement outside of conventional court systems.

Thus, the drive for a revamped NJAC is a component of a more comprehensive plan to modernize India’s legal system while juggling judicial autonomy with executive control.

Meghwal’s term has also been notable for his focus on technological integration in the court, including growth of e-courts and artificial intelligence-driven case management. Of which the NJAC discussion is only one aspect, these changes show a larger drive for efficiency and accessibility in the judicial process.

Problems and Feasibility of a New Jersey ACR

The planned NJAC will still have to overcome major obstacles even if veto power has been removed.

First, any constitutional amendment to restore NJAC would need a two-thirds majority in Parliament and then acceptance by at least half of the states. Given the political scene, getting such support could not be easy.

Second, the participation of the Law Minister in the commission could still be seen as a possible executive intrusion even without a veto.

The opposition of the court to such a system would result in protracted legal conflicts maybe ending in another review of the Supreme Court.

Clarifying the position of “eminent persons” on the commission presents still another difficulty.

Whether the NJAC can operate as an autonomous and balanced body will depend much on the standards for their choice and their impact on the decision-making process.

Any impression of political leaning or favoritism in these selections could erode the legitimacy of the new government.

An unresolved debate, or a New Jersey AC?

Meghwal’s amended NJAC plan marks a major change in the continuous reform debate as India gets ready for yet another round of debates on judge appointments.

Eliminating the controversial veto authority helps the government to resolve past grievances and guarantees a disciplined, participatory appointment system. Still to be seen, though, if the court and parliament would embrace this approach.

The government’s capacity to persuade interested parties that the new NJAC will improve rather than compromise judicial independence will determine the viability of this proposition.

If executed sensibly, it might fundamentally change India’s court appointment process. Should opposition be encountered, it might confirm the court’s inclination for the status quo, hence preserving the collegium system despite its shortcomings. In either case, the NJAC discussion is far from finished and will determine the legal scene of India for years to come.