sadhguru isha foundation

Under spiritual head Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev, the Isha Foundation has lately attracted close examination on claims ranging from sexual abuse of juveniles to attempts to censor critical media coverage. These disputes have not only begged major ethical and legal questions but also exposed more general problems in India’s legal system, including the protection—or lack thereof—for reporters covering defamation claims and Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs). We investigate the main accusations against the Foundation, the legal measures taken by and against journalists, the immediate need for anti-SLAPP protections, and issues about political and institutional bias that might be protecting the organization from complete responsibility in this thorough investigation.

Claimed sexual assault and the POCSO FIR

Parents of a former student of the Isha Home School in Coimbatore attended a news conference in Hyderabad in late October 2024 to claim that their son had been sexually assaulted by another student attending the Isha Foundation-run school. They asserted they were intentionally discouraged from reporting the situation to the police and received no help even when they protested to school officials. The Tamil Nadu police registered a First Information Report (FIR) at the All Women’s Police Station in Perur, Coimbatore, under Section 10 (aggravated sexual assault), 21(2) (failure to report an offence), and 9(1) (compensation) of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, as well as Section 342 (wrongful confinement) of the Indian Penal Code Scroll.in.

The FIR records that the claimed abuse happened between 2017 and 2019 when the lad was in Class 10. The complaint says that staff members at the school tried to calm the mother by moving the accused student temporarily only to have him back at the same hostel a week later after she threatened to approach the police. The mother noted in the FIR that staff members had downplayed the seriousness of her son’s claims and cautioned her that investigating the situation would damage “Sadhguru’s reputation” and result in “bad karma,” hence underlining psychological pressure to keep the incident under wraps.

Concurrent with this, early October 2024 saw the Madras High Court take suo motu notice of criminal complaints lodged against the Foundation while hearing a habeas corpus petition claiming two adult women were being held against their will at the ashram. The High Court ordered the Tamil Nadu government to report on all cases, including those under POCSO, and a sizable police contingent searched the Velliangiri Foothills grounds. Later, the Supreme Court halted this decision after considering the need of a broad police operation and instead directed a judicial official to personally interact with the ladies engaged in this activity. The New Indian Express Business & Finance News

The tardy FIR filing combined with claims that school officials intentionally discouraged the family from reporting the abuse show to structural flaws in child protection and POCSO implementation. The situation of the Isha Home School emphasizes the vital need of quick response and independent supervision when minors are under danger to avoid institutional prejudice from interfering with justice.

Shyam Meera Singh: Video video takedown and defamation lawsuit

Journalist and YouTuber Shyam Meera Singh released a video called “Sadhguru EXPOSED: What’s happening in Jaggi Vasudev’s Ashram?” in February 2025 Alleged to be exploitation of youngsters at the Foundation’s ashram, the video rapidly gained over 900,000 views and generated extensive debate. In response, the Isha Foundation sued for defamation in the Delhi High Court, alleging from the video “false, reckless, baseless and perseous” statements devoid of any confirmed evidence www.ndtv.com.

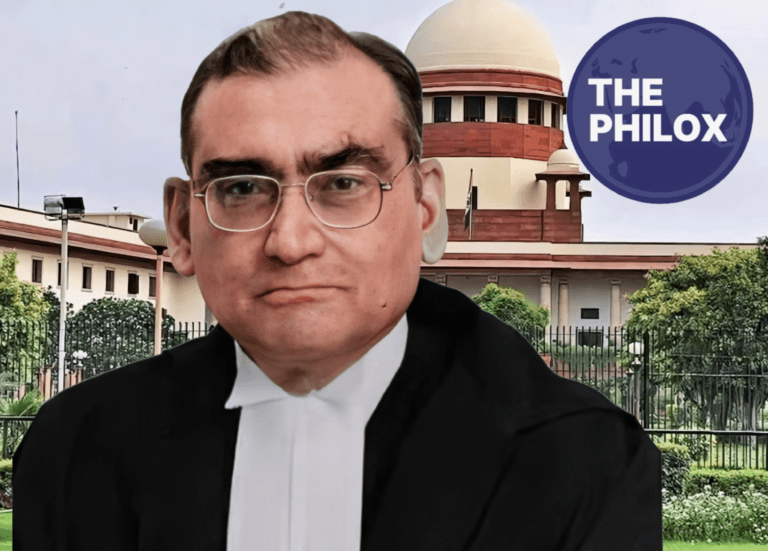

Justice Subramonium Prasad of the Delhi High Court issued an ex parte temporary ruling on March 12, 2025, mandating Singh to erase the video from all social media platforms and restrict online users from distributing it even more. Invoking Article 21’s protection of dignity and reputation alongside freedom of speech concerns, the court decided that the title and contents of the video directly affected the reputation of the Foundation. The Siasat Daily reports that the order asked Google, X (previously Twitter), and Meta to remove the video and related content until the next hearing set for July 9, 2025.

Opponents of the takedown have claimed that this ruling best illustrates how aggressively defamation lawsuits are used to stifle investigative reporting. Given Singh’s film was based on internal emails and victim testimony—albeit unverified—the court’s preparedness to grant an ex parte injunction begs questions about the balance between reputation and free expression. This case shows how defamation law can be used to reduce public interest reporting, particularly in cases when organizations with significant resources try to avoid critical examination.

The legal Notice and the Philox

Published on a media outlet devoted to investigative journalism, the Philox reported on the claims against the Isha Foundation with contextual analysis of court cases and interviews with complainants. Claiming the piece contained defamatory material, the Foundation sent a legal notification to The Philox shortly after the report went live asking for the immediate removal of the item. Should the platform fail to comply, the notification threatened legal and criminal liability, therefore pressing The Philox to back off its reporting under the fear of expensive litigation and possible fines.

This strategy reflects the strategy used against Singh and emphasizes a more general trend of intimidation of media outlets by legal letters. The Philox stands by its reporting and has said it is ready to defend the story in court; nonetheless, the stifling effect of such notices—often issued without prior independent examination of the claims—showcases the pragmatic dangers small and medium-sized media organizations face. Defending defamation lawsuits may be financially and operationally taxing, and the mere fear of legal action can discourage outlets from covering important stories about influential organizations.

The urgent need for anti-SLAPP protections

Particularly on issues of public interest, strategic lawsuits against public participation—also known as SLAPP suits—are legal actions launched to threaten or punish individuals and organizations for using their right to free expression. There isn’t yet a thorough anti-SLAPP system in India to enable judges reject meritless defamation claims at early phases. Journalists and civil society activists must so negotiate protracted legal battles bearing legal fees and proof burden even before major hearings take place.

Observing that ex parte orders to remove materials amount to a “death sentence” for public discourse unless the material is “malicious” or “palpably false,” the Supreme Court advised against the reckless grant of pre-trial injunctions in defamation lawsuits in March 2024. The Court underlined that temporary injunctions should only be given in “exceptional” circumstances where the defense would surely fail at trial and referenced English and Wales’ precedent from Bonnard v. Perryman. This historic direction advised subordinate courts to give public interest and free speech greater top priority before limiting publication.

The European Parliament’s 2024 Anti-SLAPP Directive calls Member States to implement early dismissal policies for SLAPP cases, levy fines on frivolous litigants, and pay victims of SLAPPs damages internationally. These steps seek to discourage abuse of defamation rules and safeguard reporters’ capacity to cover issues of public interest free from worry about reprisals. India’s lack of such protections leaves our media open as strong people and companies can quickly use legal notifications and lawsuits to discourage important reporting.

India has to pass particular anti-SLAPP laws if it is to protect the constitutional right to free expression and guarantee strong public debate. Important clauses should be: an accelerated hearing for claimed SLAPP lawsuits, early dismissal of bogus claims, cost shifting to punish unfounded plaintiffs, and protections for digital intermediaries to oppose takedown demands. Defamation and legal notifications’ stifling effect will keep erasing India’s robust press and civil society without these changes.

Institutional and Political Shielding

Beyond legal wrangles, there are rising worries about central authorities and law enforcement agencies giving the Isha Foundation too much protection because of its strong relations to the Modi government. Critics cite multiple cases when high-level actions limited local investigations or expanded Foundation-approved judicial interpretations.

Following the Madras High Court’s directive on a police investigation into all criminal allegations against the Foundation in October 2024, over 150 Tamil Nadu police officials—including DSPs and an Additional Superintendent—perused the ashram grounds in great care. This strong measure looked out of line for usual reactions to habeas corpus petitions involving adults. But within days the Supreme Court stopped the investigation, voicing worries about the scope of the police operation and sending the case to a judicial official, therefore restricting police access and control Business & Finance News The Indian Express.

The Coimbatore Police also sent the Supreme Court a 23-page status report comprising POCSO claims and missing persons detailing 15 years of cases connected to the Isha Foundation. Of the six missing person cases, just one is still under inquiry while five were closed. Two of the seven cases under Section 174 CrPC—police investigations into unnatural deaths—still awaited forensic findings. Among these was a complaint of sexual assault reported as a zero FIR in Delhi during a yoga training, then retracted by LawChakra.

The Madras High Court dismissed the Tamil Nadu Pollution Control Board’s show cause notice alleging illegal building between 2006 and 2014 at the Coimbatore site in 2022 on grounds the Foundation qualified as a “educational institution.” The Supreme Court maintained this quashing and chastised the Board for its belated appeal in March 2025, asking why the state body delayed suing against the High Court ruling two years prior. Some have seen the Court’s emphasis on the Foundation’s compliance assurance and ban on coercive action as evidence of institutional partiality.

The Times of India; Hindu Times

These well-publicized court actions along with little follow-through on police and regulatory investigations point to a safe surroundings for the Isha Foundation. Although Sadhguru’s group insists that all activities are legal and voluntary, the look of political and institutional cover begs issues about responsibility and equal application of laws—two pillars of India’s rule of law.

From the POCSO FIR against school staff to defamation lawsuits targeting journalists, legal notifications to minor media outlets, and alleged political shielding, the several debates around the Isha Foundation reveal systematic problems in India’s legal and institutional systems. Free speech and public interest reporting suffer greatly from the readiness of strong entities to use defamation litigation and SLAPP‑style legal strategies. Concurrent with claims against the Foundation, judicial and regulatory reactions have occasionally seemed more protective than investigative, hence fostering impressions of prejudice.

Dealing with such problems calls for a two-pronged strategy. Regardless of the accused institution’s power, India has to first improve child safety systems and guarantee fast, open investigation of POCSO allegations. Second, thorough anti-SLAPP laws are desperately needed to shield media sources and reporters from pointless legal action meant to silence them. India can defend its constitutional ideals and keep public confidence in its institutions only by strengthening both substantive protections for minors and procedural safeguards for free expression.